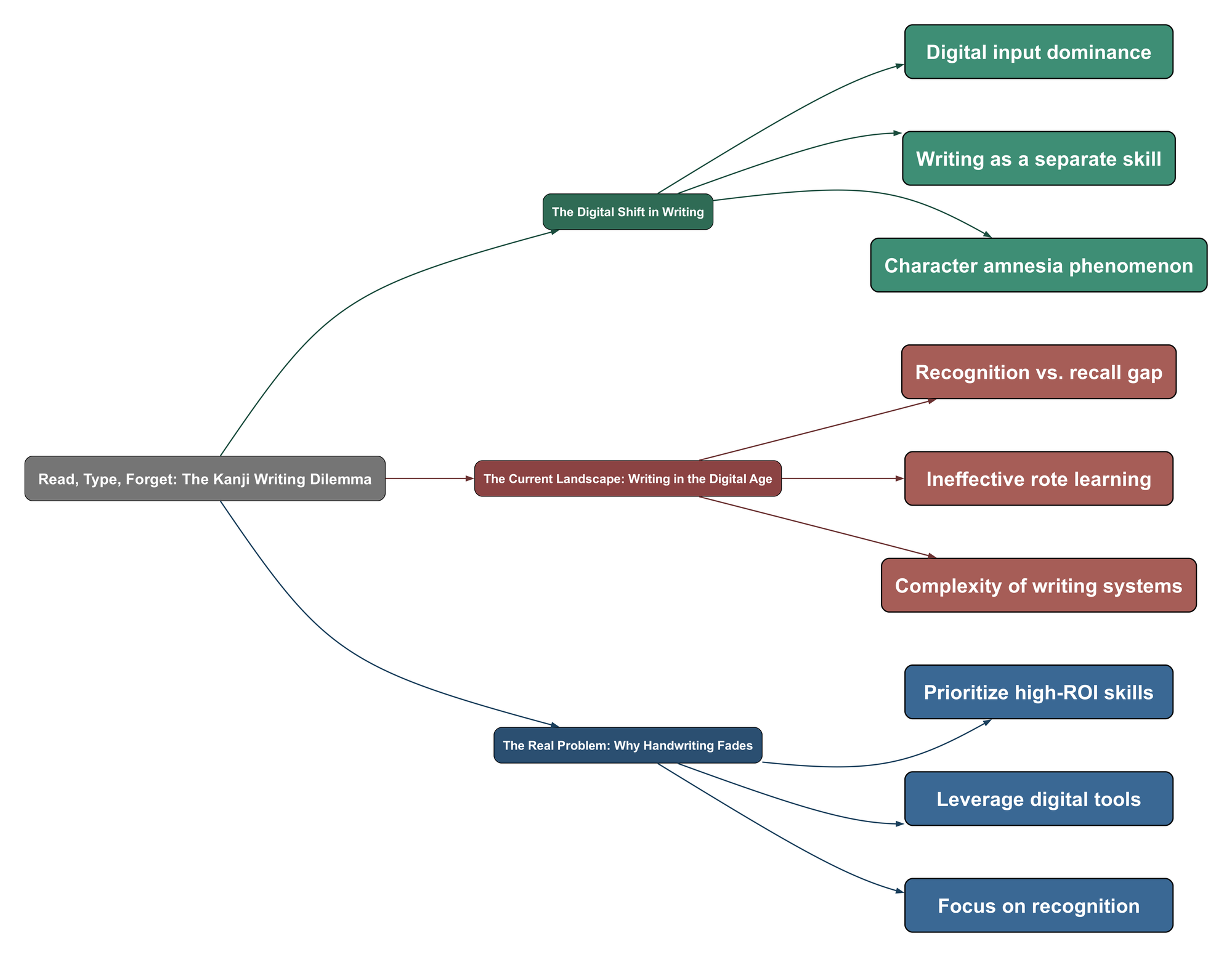

The Digital Shift in Writing

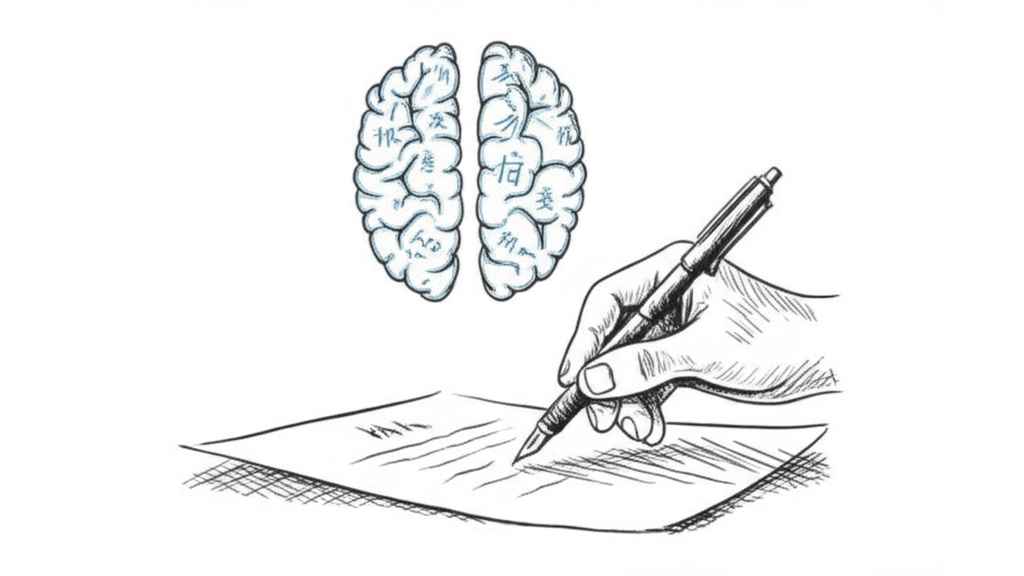

Ever stared at a blank form, phone in hand, trying to remember how to write a character you can instantly recognize on a screen? This digital-age amnesia, especially common with Japanese Kanji and Chinese Hanzi, isn’t just a learner’s problem—it’s a widespread phenomenon affecting natives and experts alike, driven by our reliance on technology.

The Current Landscape: Writing in the Digital Age

The way we interact with complex writing systems has fundamentally changed. The muscle memory required for handwriting is being replaced by the convenience of phonetic input systems and digital keyboards. This shift has created a new reality for language users everywhere.

- Digital Input is the Norm: From the early dedicated ワープロ (Word Processors) in Japan to modern smartphone keyboards, typing has become the primary method of writing. This is true for both logographic and alphabetic languages.

- Reading and Writing are Separate Skills: Learners and even native speakers are increasingly realizing that reading comprehension and handwriting are distinct abilities. Many now strategically focus their efforts on reading and typing, skills with a higher daily utility.

- A Universal Phenomenon: The issue isn’t unique to Japanese. In China, it’s known as 提笔忘字 (tíbǐwàngzì) — “to pick up the pen and forget the character.” It’s even analogous to a common struggle in English.

The western equivalent of being able to read some kanji but not write them is simply called bad speling. No need to mystify kanji in particular.

The Real Problem: Why Handwriting Fades

The gap between passive recognition and active recall is a major cognitive hurdle. While our brains are excellent at identifying patterns we’ve seen before, constructing them from scratch is a far more demanding task, one that atrophies without constant, deliberate practice.

- Complexity Demands Practice: Logographic systems, with their thousands of characters, require immense and continuous effort to master by hand. Without the daily necessity of writing, this skill quickly diminishes.

- Recognition Isn’t Recall: The ability to recognize a character is fundamentally different from being able to reproduce it from memory. This is a general characteristic of the human brain, applying to everything from song lyrics to drawing from imagination.

- Rote Learning is Insufficient: Simply memorizing characters through methods like flashcards (Anki) or mnemonic systems (Heisig) often fails to translate into practical writing ability without real-world application.

I went through Heisig’s book THREE times, writing out each character and reviewing them multiple times each in Anki… I still can’t write most kanji. The fact is that you simply cannot learn to write without practicing writing (in real contexts, outside of the notebooks).

The Path Forward: Adapting to a New Reality

Rather than viewing this as a failure, many are reframing it as a logical adaptation to modern life. The solution lies not in fighting the tide of technology, but in embracing smarter, more efficient strategies for language proficiency that align with today’s needs.

- Prioritize High-ROI Skills: Many learners consciously choose to skip handwriting to focus on more practical skills like speaking, listening, and reading. This maximizes the return on their limited study time.

- Leverage Technology as a Tool: Using a phone to look up a character when filling out a form is no longer a sign of failure but a practical, modern solution. Digital tools are an extension of our memory.

- Focus on Recognition and Systemic Understanding: The most valuable skill for most is visual recognition. Understanding how characters are constructed (e.g., radicals) aids in reading and vocabulary acquisition, which is more critical than the ability to produce characters by hand.

When I need to go to fill forms I flip up my phone and search for Kanji all the time. And I know I’m not alone… I can navigate Japan just fine.